We are now well past Canada Day, the date that the federal government had previously promised to remove our internal trade barriers regarding wine shipped and sold between provinces. We have no actual substantive progress to date – merely some vague announcements and promises to negotiate. It appears, unsurprisingly, that the government was too optimistic in thinking that the provinces would cooperate on this endeavour. This article explains the background to the relevant issues and why it will be hard to obtain meaningful provincial buy-in. As you will read below, the basis of the problem is the province’s reliance on liquor markup as a significant source of government revenue. In my view, this is one of the most significant long-term impediments to the health of Canada’s wine businesses.

1. What Are Liquor Markups?

In most jurisdictions, governments raise revenue from wine sales by imposing excise taxes at the wholesale level which are usually volume based. They may also include alcohol sales as part of their general sales tax systems which are usually percentage based. Many governments do both of these things, like Canada’s federal government which imposes a 5% GST on all wine sales as well as an excise tax which is currently set at $0.73 per litre. These taxes are relatively transparent because they are well publicized and need to be approved by Parliament.

However, the Canadian provinces take a somewhat different approach because each holds a statutory government monopoly over all liquor distribution within that province. As part of the ‘business operations’ of that monopoly, the province can impose ‘liquor markups’ on to all products sold within that province. These markups are not taxes so they do not need to be approved by each legislature. Often, they are not well publicized or transparent. Most commonly, the markups are calculated by adding a percentage based amount to the value of the product as a wholesale markup (e.g. in BC, the base markup is 89% of the supplier cost for wine). But sometimes, a volume based amount is added (e.g. in AB, the base markup on wine is $4.11 per litre). In some provinces like BC, there are both wholesale and retail markups, the latter of which are applied within government retail stores.

To a small extent, these liquor markups cover the costs of operating the liquor distribution system in each province. But mostly they are imposed simply to generate extra revenue for government. In other words, they are hidden taxes. What are the effects of and issues with this system?

2. Government Relies on the Hidden Tax Revenue

The first major effect is that each provincial government becomes dependent upon the liquor markup revenue that is collected by its liquor monopoly. For example in BC, the LDB sold $3.9 billion worth of liquor in its fiscal year ending in 2024. After deducting cost of goods sold, its gross profit margin was $1.7 billion. Operating expenses totaled $569 million for a net profit of just over $1.1 billion. In Ontario, the LCBO contributed $2.4 billion to provincial coffers for a similar time period. These amounts are a major contribution to provincial finances and make it difficult for government to objectively assess liquor policy reform.

3. The Markups Increase End Consumer Prices

The imposition of liquor markups increases costs throughout the supply chain. So if a monopoly imposes a high wholesale level markup (tax) on wine, the end consumer will end up paying a higher retail price for their bottle of wine. The extent of this effect varies considerably from province to province depending upon how they calculate and apply their markups. As a general rule though, because the liquor markups are designed to provide high amounts of ‘hidden tax’ revenue, the prices for wine in Canada are high compared to most of the western world and very high compared to other historic wine producing nations.

This poses a challenge for the development of wine and food culture both at retail and in hospitality (restaurants, bars, hotels). It also encourages black and grey market sales as consumers seek to buy at prices that are more competitive. Generally, the lowest markups on wine (particularly higher priced wine) have been applied in Alberta which uses a volume-based markup system described above. Provinces that use high percentage based markups (like BC) generally have the highest end-consumer prices.

The variability in markups is why wine prices differ so much from one province to another. In addition, most provinces except AB apply provincial sales taxes to wine, which generates additional revenue for government and further increases costs for consumers.

4. The Markups Discourage the Marketing and Promotion of Wine

The marketing and promotion of wine within the Canadian system is challenging because, generally, the provincial liquor monopolies apply their liquor markups to almost all wine products that move through their systems … even if those wines are being used for marketing and promotional purposes, rather than being sold to end consumers. This means that it is more expensive to promote and market wine in Canada than in other places in the world.

For example, even if a winery wishes to donate wine for marketing and promotion purposes (e.g. for a wine festival or trade fair), the importer will still have to pay the liquor markup. In most other places, any taxes/fees for such activity would be minimal but in Canada the liquor markups make it expensive to do such marketing. Historically, the only respite from this was to use ‘consular privilege’ (i.e. have the consulate from the wine producer’s country sponsor the marketing event and import the wine as consular wine) but this has become difficult if not impossible due to recent federal and provincial policy changes.

5. Creation of Exemptions from Markup for Local Producers

The existence of the markup system has proved to be detrimental to the development of Canada’s local wine industry. Canada’s domestic wine industry is young. Capital costs, land costs, and operating costs are high. This means that the base ‘supplier cost’ for wine produced in Canada is already high by global standards. If provincial liquor markups were added to that cost then, very frequently, the end consumer price for the wine would be too high and would be uncompetitive.

As a result, most provinces have felt compelled to provide local subsidies or preferences in order to encourage local industry. This has usually been done by reducing the effect of the markups on local wines either by exempting them from the markup entirely (BC) or by applying reduced rates of markup (ON).

While this has encouraged local industry, it has ancillary consequences: 1) In the local market, domestic wine is competing with imported products that are subject to higher mark-ups (and higher prices). While this benefits domestic wine, it makes it harder to export that same wine because as soon as the wine is outside the local market, it is competing with the same or similar wines that are priced much lower. 2) Most international trade agreements prohibit preferences which distort end consumer pricing. In contrast, direct subsidies aimed at agriculture or innovation are usually permissible. As a result, it is arguable that the approach of the provincial liquor monopolies is not trade compliant. Indeed, Canada has been found to violate some of our trade agreements for exactly this reason. These trade issues pose an ongoing threat to the system and to local producers. 3) Most provinces only provide their local preferences to their own provincial wine. Wine from other provinces is not provided with the same preferences. This is the main cause of our internal trade issues discussed further below.

Such issues become even more complex when unusual circumstances arise. For example, the recent climate related crop failure in BC has caused the BC Government to allow local wineries to obtain markup exemption even when they are using imported (mostly U.S.) grapes, which raises further trade compliance issues.

6. Problems with Inter-Provincial Trade

Each Canadian province has an alcohol regulation and distribution system that largely treats the other provinces (and their consumers) as if they were in foreign countries. As noted above, liquor markups are applied to wine from other provinces just as if that wine was imported from abroad. The regulatory structure is parochial in nature since there is virtually no recognition that other provinces’ Canadian wines should be recognized as ‘domestic’ product.

The heart of the problem is that each liquor monopoly maintains a ‘control’ mentality in order to ensure that it continues to collect the liquor markups that generate the large cash payments for its political overlords. Each monopoly is worried that its existence will be questioned if it is unable to maintain (and preferably increase) those payments. This is why most provinces still attempt to ban or restrict alcohol sales and shipment from other provinces … they are worried about losing their liquor markup revenue on those sales.

In this respect, markups have historically been worse than tariffs for the interprovincial trade in wine … because rather than creating a system that would permit the collection of the markup (and/or reducing the markups to more reasonable levels), the provinces instead made it illegal to make those interprovincial shipments … forcing wineries and consumers to break the law if they wanted to buy wine from another place within Canada.

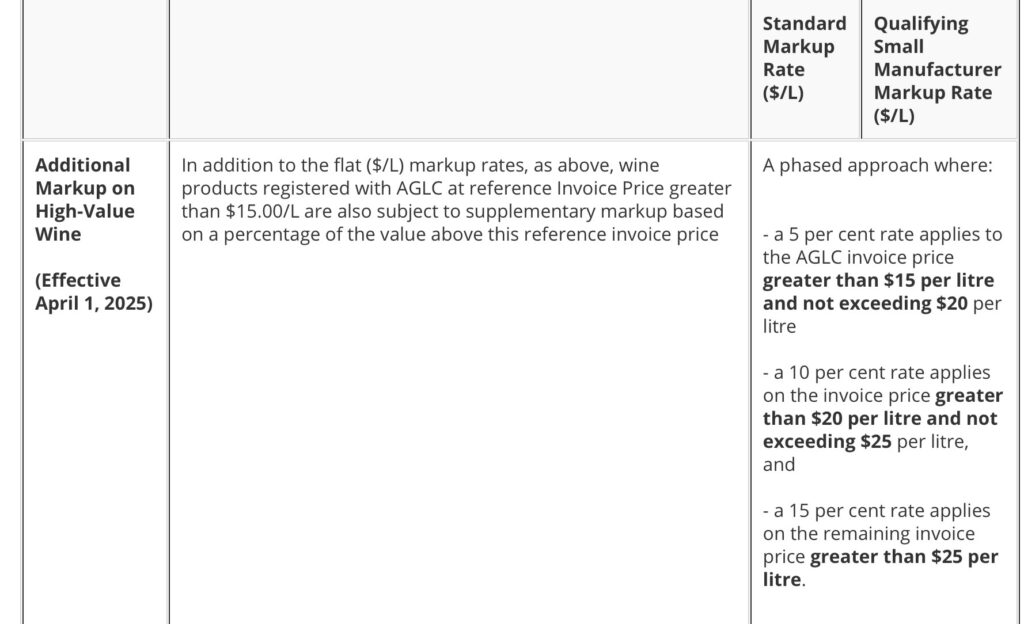

A few provinces have changed their laws to some extent over the years. For example, Manitoba allows all such interprovincial shipments and has done so since 2012 when the federal law changed. BC and Nova Scotia allow such shipments if they consist of 100% Canadian wine and are shipped from the producing winery. Saskatchewan and Alberta allow the shipments if the markup is collected using complex permitting systems. But in the latter case, and as of April 1st, the Alberta government has moved from a relatively simple flat rate system to a more complicated one with higher markups that is going to be challenging for both wineries and consumers to accept. The other provinces and territories still maintain blanket bans.

This is a ludicrous situation which completely holds back the development and expansion of Canadian wine businesses by preventing consumers from patronizing any such business that is not located in their home province. Imagine if it was illegal for someone in Paris to purchase wine from a winery in Bordeaux? Or against the law for a consumer in Rome to buy wine from Tuscany?

In this respect, it is important to note that Manitoba (the only fully open province in Canada right now) has reported no problems with their open borders policy and has seen no appreciable drop in liquor markup revenue as compared to other provinces.

7. Reform of Liquor Markup System

The above discussion highlights the issues with the implementation of and the reliance upon liquor markups by the various provincial governments. In an ideal world, it would be beneficial to re-think this system and come up with something better. However, this will be challenging. Here are some ideas and reasons why it will be tough.

A. Switch from percentage based markups to volume based markups.

Most wine producing jurisdictions use volume-based excise taxes to raise money from alcohol sales. Alberta’s volume-based markup system was the envy of the Canadian wine business until recently. For about 3 decades, Alberta’s approach created a vibrant retail and hospitality market for wine with reasonable prices, great consumer selection and consistent government revenue. About a year ago, the system was also extended to allow DTC sales for BC wineries (upon payment of the markup – about $3 per bottle). This would have created a smart national precedent for a workable and relatively open system. Unfortunately, Alberta has recently backtracked (in the hope of raising more money) and introduced an additional percentage based liquor markup on “high value” wine which will raise consumer prices and which makes the DTC system so complex that it is unworkable.

In my view, it would make more economic sense (and create a healthier wine marketplace across the country) if the provinces all switched to volume based markups (and for AB to switch back). However, this is a fundamental change which would require considerable work within the liquor monopolies.

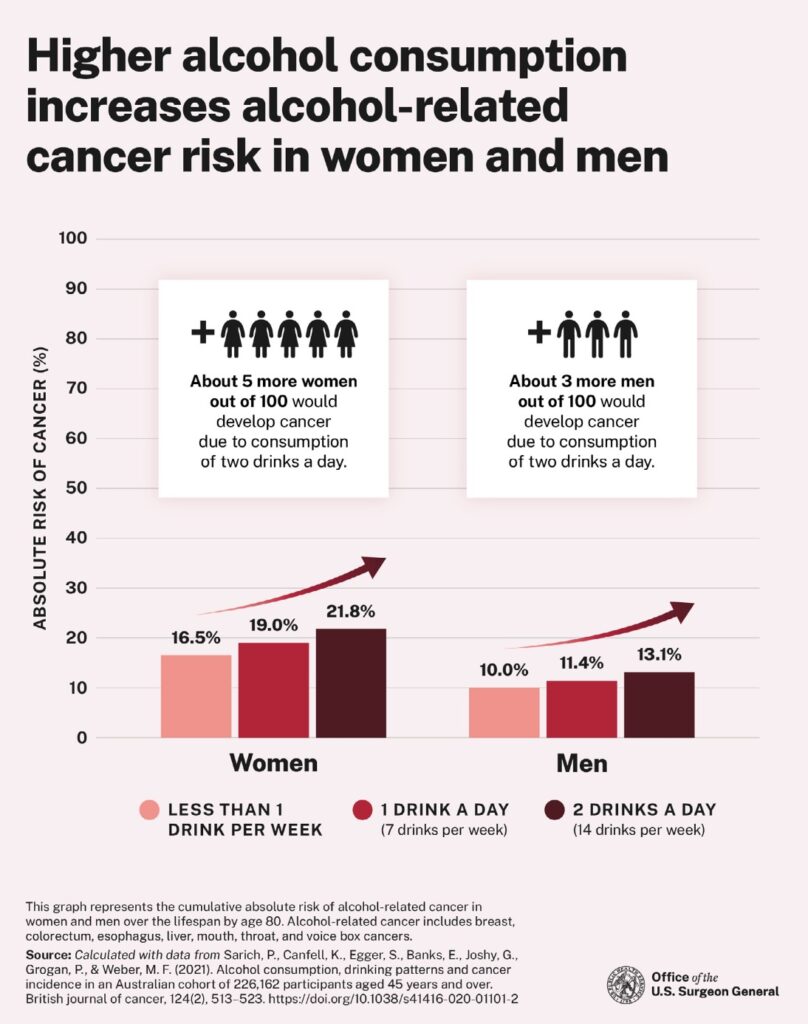

B. Realistic levels for the markups

Liquor monopoly sales are falling due to reduced consumption. It’s unlikely that the monopolies can meaningfully reduce their operating expenses. This means declining revenue for government unless the system is restructured. At the present time, the percentage based markups are simply too high and it’s hard to increase them. They create consumer resistance, stifle the growth of food/wine culture, hurt hospitality/retail businesses, and encourage grey or black market sales. The imposition of volume-based markups at a reasonable level would restore overall health to the system … and enable government to maintain revenue without adversely affecting end consumer prices.

In addition, the use of percentage based liquor markups on trade samples and wine imported for marketing purposes actively discourages the promotion of the wine business and the development of wine culture. A volume-based system would make such costs more reasonable.

C. Some Commonality of Markup Levels Would Solve the Internal Trade Issues

If the provinces switched to volume-based markups en masse and at a relatively consistent tax level, there would be little incentive, between provincial marketplaces, for consumers to buy in a different province. This would enable the provinces to accept a personal use exemption for all interprovincial wine sales, either free of markup for all such transactions or at a commonly agreed upon reasonable level.

****

However, government’s quest for more money and continued control will probably over-ride all these concerns as we have recently seen in Alberta. In addition, how likely is it that the provinces can be persuaded to adopt blanket and more consistent pricing reforms … and mostly at the same time? The unfortunate reality is that bureaucratic opposition and political inertia will likely doom any significant reform efforts … and that the best we will see is a half-baked DTC system in a few provinces that is too expensive and complicated to work.

It remains my view that the only real likelihood of change is for the federal government to legislate a solution as I previously explained in an earlier post (last two paragraphs of DTC Canada vs USA – a Tale of Unfortunate Contrast): the federal government should exercise its exclusive jurisdiction over interprovincial trade and legislate a national personal exemption amount for interprovincial wine sales. Yes, the provinces would probably object (and might go to court) … but as we have seen from Manitoba, there would be little significant effect in the long term … and once the gates are open, they will likely stay open.

Canadians deserve much better than the absurd status quo on this issue … and it is long past time for Canada to “free its wine”.